Table of contents :

Part I: The Tōei era

Part II: From one studio to another

Part III: From animation to Nintendo

Part IV: Diversification and transmission

Part V: Towards new horizons

Sources

Appendix : Works on which Yōichi Kotabe has worked

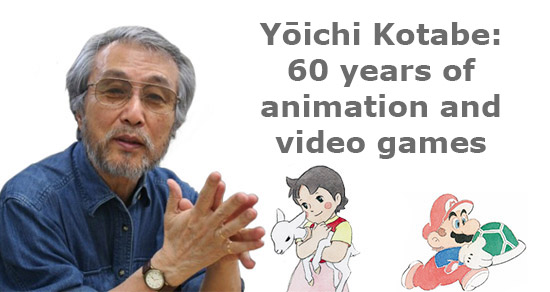

After spending a quarter of a century in the field of animation and building a resume that still evokes memories for the general public, Yōichi Kotabe could have continued his path in the industry and, like many of his peers and friends, moved on to directing. However, rather than take the plunge, he chose to branch out into a sector that was still in the making, leaving his mark on another part of pop culture and defining the appearance of some of its most famous icons in the process.

A versatile character known to both video game and animation enthusiasts, he is one of the main symbols of the porosity between these two fields, as much by his work as by the influence he has had on both industries. Although his work at Nintendo was little publicized during the time he was employed there, he occupied an important place within the company, designing or refining some of its main characters during the 2D era, and then contributing greatly to shaping them in 3D from the second half of the 1990s. Moreover, although he is better known for the characters he drew and sometimes animated, one of the aesthetics he developed to represent the ocean has subsequently been used in animated films and series as well as in video games. Therefore, it seemed important to us to retrace his entire career and to map the bridges between these two fields, which are too often discussed in a compartmentalized manner.

In one field as in the other, credits can be very incomplete or even misleading, and the following article will unintentionally overlook certain parts of his career that the author of these few lines didn't manage to learn about. Unless otherwise indicated, the following quotes are from Yōichi Kotabe.

Born in Taipei on September 15, 1936, Kotabe spent part of his childhood in Taiwan at a time when the island was a Japanese colony. During these early years, he discovered propaganda animation films produced by the Japanese government, including two short movies released in 1943 that made a particular impression on him, not because of the message they conveyed but thanks to their visual aspect: Kumo to Tulip, for its spider character, and Momotarō no Umiwashi, from which he retained the aerial sequences as well as the rabbit characters, which he would later describe as the source of his desire to animate characters.

Kumo to Tulip and Momotarō no Umiwashi

After the defeat of Japan and the return of Taiwan to the Republic of China, his family was repatriated to Japan on an American transport ship. In the years that followed, Kotabe spent much of his free time reading manga and reproducing drawings, especially those of Osamu Tezuka.

"In particular his works from his first period, such as Shin Takarajima (1947) and Lost World (1948), the first parts of his thematic trilogy around science fiction. Tezuka's drawing, also inked, had a roundness, a suppleness and a warmth. There too, one had the impression that the characters were alive, and I imitated his drawings with a lot of energy myself."

Drawings made by Kotabe at the elementary school

By his own admission, Kotabe didn't really care about his schooling, finding it more fun to draw during class or even to animate stick figures on improvised flipbooks. He also spent some of his spare time watching animated films, especially Disney productions. However, the latter were slow to be released on the Japanese territory, as the Ministry of Finance and the Japanese government implemented a protectionist policy that strongly limited the import of foreign films on their territory. It was not until 1950 that the Burbank studio's animated films were released in the archipelago, starting with Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, for a total of 8 films from that date to 1956.

In a Japan in reconstruction, Kotabe saw animation as his main source of entertainment. However, he did not immediately consider becoming an animator. His father, who was an oil painter, encouraged him to study fine arts.

"I really started drawing in middle school and I had hopes of getting into the drawing business. There were few ways to do that at the time, but a friend of mine convinced me to take the entrance exam for the Tokyo Art School. I became familiar with oil painting, but I was not interested in it. I quickly moved on to something else, such as watercolor, and was inspired by the classical Japanese school of painting."

While Kotabe intended to become a painter, an event occurred during his studies. In 1956, the production studio Tōei decided to open a department dedicated to animation films called Tōei Dōga (later renamed Tōei Animation). This animation studio embarked on the production of the first full-length color animation film made in Japan: The White Snake Enchantress / Hakuja Den. In addition to its status as a precursor, this film released in 1958 demonstrated that there was a way other than the one adopted by Disney. For Kotabe, it was such a shock that he decided to reorient himself.

"I saw it as a student and was thrilled. I'd grown up watching Disney animation and had always thought that Japan's animation wasn't worth much. But when I saw The White Snake Enchantress, I changed my mind. I was moved to see that Japan could make something so incredible. So anyway, Tōei Dōga started recruiting."

The White Snake Enchantress, a film that influenced many of the animators of Kotabe's generation

Kotabe applied for the entrance exam to the Tōei Dōga studio, which was recruiting from art schools at that time. The new recruits were then trained within the studio and learned by working.

"I invited two of my classmates. I said, 'If you can't find a job, let's do animation together!' They had no interest in manga at all and didn't even know what animation was. But they ended up getting the job, and I didn't! (laughs)

I was certain I would be accepted, so I had no idea what to do. I had really been excited about joining Tōei Dōga, so I was crushed. But Tōei was on such a roll then, it wasn't long before they started recruiting again. I applied and was barely accepted."

Kotabe was part of a selection that included Isao Takahata and Hiroshi Ikeda, 2 directors close to the future animator and whose path he will cross many times during the decades that follow.

As soon as he entered the company in April 1959, he followed a 3-month training period:

"We were under the guidance of the animator Masao Kumagawa. He gave us examples and asked us to find the same rendering of the lines."

At the Tōei Dōga studio in the early 1960s

After this training, Kotabe joined the team of a person who had pleaded in his favor with the management at the time of his second entrance exam: Daikichiro Kusube, one of Tōei's key animators.

At that time, the studio had about ten key animators, each of whom was in charge of a team of 6 or 7 inbetweeners. Kotabe started as an inbetweener, a position that consists of drawing all the intermediate images between 2 key poses. This position is generally considered as the first step in the career of an animator, the one where he acquires or consolidates the basics.

In black, the key poses drawn by the key animators. In cyan and red, the in-betweens drawn by the inbetweeners

"Newcomers like myself worked as hard as we could at taking what they had done, cleaning it up, and drawing the frames that would come in between.

After about three years you begin to understand movement and are able to start drawing it yourself."

He thus worked on the film Shōnen Sarutobi Sasuke (1959), then on Saiyūki / Alakazam the Great (1960), a feature film adaptation of Osamu Tezuka's manga Boku no Songoku (1952-53), itself adapted from the novel Journey to the West. The project was initiated in 1958 and co-directed by Taiji Yabushita (who already held this position on The White Snake Enchantress) and Daisaku Shirakawa. Tezuka, a film enthusiast who came to comics somewhat by default, participated in the development of the storyboard, thus beginning his collaboration with the studio Tōei. He later repeated the experience on the films Sindbad no Bōken (1962) and Wan Wan Chūshingura (1963).

Despite the rivalry between each of the teams, some animators from other teams became noticed by their peers. One of them was Yasuo Ōtsuka. The man who would become known to many anime fans for his contributions to the animated adaptations of Lupin the Third was not shy about offering advice to all, disregarding the organizational system adopted by Tōei. While he had to animate a tiger, Kotabe witnessed a demonstration performed by Ōtsuka after having already observed the way Kusube, the leader of his team, did it.

Ōtsuka also produced and distributed within the studio a book merging several English-language books on animation techniques, especially those used at Disney. He was also the leader of the first (and only) union formed within Tōei and in which Kotabe took part.

After continuing his work as an inbetweener on the films Anju to Zushio Maru / The Littlest Warrior (1961) and Sindbad no Bōken / Sinbad the Sailor (1962), Kotabe drew his first key animations on the film Wanpaku Ōji no Orochi Taiji / The Little Prince and the Eight-Headed Dragon, for which Yasuji Mori held the position of animation director. The task of an animation director is to ensure consistency in the animation and character designs and to review all shots for corrections if necessary. It seems that this position (which can be shared by several people on the same work) has formally appeared in Japan with this film.

Mori is considered a mentor by a number of animators and directors of Kotabe's generation, be it Hayao Miyazaki, Isao Takahata or Kotabe himself. He was among those who worked at Nichido Eigasha before joining Tōei when it founded its animation studio, where he notably supervised half of the training shorts during its early years. Unlike other animation directors who seek to impose a homogeneity of style on the various animators working on the same film, Mori allowed the style of each to express itself more freely. However, he had a notable stylistic influence on Kotabe, the latter having inherited the simplicity of his line and his round drawings.

In addition to the key frames that he had to produce for certain scenes (although he was simply credited as an inbetweener), Kotabe was entrusted by Mori with the task of designing a flying horse, a curvy character without any joints.

Poses drawn by Yōichi Kotabe (center) for the prince's horse.

"Our Prince of Wampaku was based on Japanese mythology, so we decided to design the character based on the haniwa (clay tablets). Thus, he has a long body and short legs."

Nearly four decades after the film's release, many people have noted that the game The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker bears some stylistic similarity to the Tōei Dōga movie, even going so far as to credit Kotabe with the artistic choice. Yet the latter denied any involvement on his part:

"Everyone tells me that I influenced them, but I have no direct connection with this game! [...] I suspect that the Wind Waker team had seen (Wanpaku Ōji no Orochi Taiji)."

On the left, the prince of Wampaku. On the right, the Link designed for Wind Waker by Yoshiki Haruhana.

The same year that Wanpaku Ōji no Orochi Taiji was released Wan Wan Chūshingura / Doggie March in Japanese theaters. Kotabe worked again as a key animator on this production and met a young beginner named Hayao Miyazaki:

Miyazaki : "In our group, Kotabe drew the key animation for Wan Wan Chūshingura. He always came to work later than the rest of us. I imagined that it was all right to come late when one was a key animator. To me, Kotabe was someone above the clouds. When I was drawing the in-between animations, two women were scrutinizing my work before it reached Kotabe. By the time it passed through these women and made it to Kotabe, there was no trace of the pictures I had drawn. [laughs] When Kotabe looked at a sequence and said something like 'it looks good', it wasn't what I had drawn at all, so how could he know whether my work was good or bad? That's the memory I have."

In 1963 began the broadcast of a TV series that has left a lasting impression on the animation industry: Tetsuwan Atomu (Astro Boy), an adaptation of a manga by Osamu Tezuka made within the studio he founded 2 years earlier - Mushi Productions - and which had in its ranks defectors from Tōei Dōga. Both a success in terms of audience numbers and a work with a limited budget, the series made people realize that Japanese animation could make a place for itself on the small screen.

Nowadays, the television productions of Tezuka's studio are often perceived negatively because of their technical aspect; the animators, in very limited number on each episode, managed to produce a 20-minute episode per week at the cost of long working days and an animation limited to 4 or 5 frames per second, where Tōei's movies had 12 at that time. However, it is important to point out that within Tōei Dōga, this series was not unanimously viewed negatively and that television in general may have appeared as a new field of experimentation, arousing the curiosity of some animators. The studio's parent company had produced live-action series in the past and when it asked its animators if they would like to work on its first animated series rather than on a film produced at the same time -Gulliver's Travels Beyond the Moon- many answered the call, including Kotabe.

The series Ōkami Shōnen Ken hit Japanese television screens in late 1963, a few months after Tetsuwan Atomu. Within the production team, we find some of Kotabe's closest collaborators: Isao Takahata, who directed several episodes, Hayao Miyazaki, then a simple inbetweener, or Reiko Okuyama in key animation, while Kotabe himself designed a number of secondary characters. Okuyama (who became Kotabe's wife the same year) described television as a "side activity", as opposed to cinema which she saw as her "real job".

During the following years, Kotabe worked on a few TV series: Shōnen Ninja Kaze no Fujimaru (1964-1965) on which he was the animation director from its 49th episode after having co-animated many episodes, Hustle Punch (1965-1966), a series that gave him the opportunity to collaborate with Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata in parallel to the production of Horus, Rainbow Sentai Robin (1966-1967), adaptation of a manga by Shōtarō Ishinomori, or Mahōtsukai Sally (1966-1968). With the exception of the last one which switched to color from its 18th episode, these series were then in black and white.

Drawing by Yōichi Kotabe for the series Shōnen Ninja Kaze no Fujimaru (presumably for its opening)

In 1965 started the production of Horus, Prince of the Sun, a project that was supposed to become Tōei Dōga's 10th feature film and that remains one of the most famous animated films of this period to this day. Nevertheless, it had an eventful production, the scene of a power struggle between the film's team and the studio's executives. At that time, Isao Takahata was very involved in the studio's union, like Ōtsuka and Miyazaki. As the director and writer on this project, he was also seeking greater creative freedom.

"(Isao Takahata) wanted to give everything with Horus because, from that time, we were in an evolution of the studio that suggested that this project might be the last. Horus was both his first feature film, but perhaps also his last chance to defend a creative ambition through this format that was already in a form of decline at the studio."

Originally set within the Ainu community, from which it takes up a legend, the story underwent a certain number of modifications due to the reluctance of the management to tackle a subject that was then sensitive in Japan. The Ainu were colonized by Japan, which pursued a policy of assimilation, one of the consequences of which was the negation of their culture and their difference, a subject that was at the heart of current events at the time the film was produced. At the instigation of studio president Hiroshi Ōkawa, who was seeking to open up to the international market, the story was transposed to a region more akin to northern Europe, but with elements from the original version, notably the costumes, inspired by those of the Ainu.

Another topical subject, Takahata saw in Horus an echo of the Vietnam War:

Takahata: "There was a sense of crisis and danger in Japanese society at the time, due to the Vietnam War. The possibility that the United States would not win this war was not excluded, and Japan, its ally, risked being dragged into this conflict."

Two films were in production at Tōei Dōga at this time, but it was Horus that Kotabe chose. He reunited with many of his regular collaborators, from Yasuji Mori to Hayao Miyazaki to Reiko Okuyama and Yasuo Ōtsuka, in the team.

Animators were invited to submit character designs and ideas. As a result, several animators were able to come up with their own version of the same character.

"When we were working on Horus (a union-led project), there was an impetus to 'Let's do it together!'. Everyone who read the script drew their own characters and displayed them in a small room.

Among them, Hayao Miyazaki is the only one to have drawn both backgrounds and animation. I didn't know how to draw anything other than characters.

An unused version of Hilda and the final version of Chiro, both drawn by Kotabe

In general, in Japan, the division of work between animators is done by shot (which can lead an animator to animate alone an entire scene or even an opening), while in the United States we share the characters to animate.

Kotabe was given the task of animating the scene of Horus' departure at sea and the wedding scene.

"Until this film, I had few constraints. I exaggerated the expressions of the characters, I made them make movements that were good but not really justified. This time, it was impossible. For this film, the director had given us very precise guidelines. Until then, the system was based on the freedom given to the animators rather than on a single leading personality. On the contrary, Mr. Takahata thought according to a logic of completion of the work around unity. He had precise demands, based on the search for coherence. The fact of having constraints stimulated us. It made us progress. To meet his expectations, we had to surpass ourselves. We couldn't just do things on the spot."

In the movie Horus, the sea is an element that, in Kotabe's words "represents an obstacle, the harshness of the world the characters are going to face". He had to give it a shape and animate it in a way that fits the world of the film.

While he had already tackled this natural element on the film Wan Wan Chūshingura, the work to be done on Horus turned out to be way more complex.

"For Horus, the order that was given to me was waves that had a certain reality. It was a terrible pressure for me and an extremely important volume of work. I spent 5 months, hours and hours of work, to animate a single shot of the film. Fortunately, even though Mr. Ōtsuka animated other shorter shots where waves appeared, this difficulty ultimately affected only one animator on the team."

In the absence of references, he went to the seaside to observe the movement of the waves. Closer to his home, he also observed the movement of the water in his bathtub.

Key frame designed by Yōichi Kotabe for Horus. Due to the size of the waves, a good part of the frame must be animated

The film was an ordeal for the whole team and had a gestation period of 3 years. It also underwent cuts imposed by the direction explains Takahata:

"We had to give up integrating scenes that we were keen on, and the management imposed a reduction in the length of the film. Its finished form of 82 minutes is short, if you compare it to the length of my other films, around 100 minutes each. There was a kind of recklessness in wanting to put so much into such a short format."

Although it did not meet with success upon its release, Horus has nevertheless built a solid reputation over the years.

Having climbed so high, many of the team's animators felt the need to move on to a lighter, more recreational project.

"Takahata was a very demanding director, very restrictive on the work of the animators, explains director Kimio Yabuki. With Puss in Boots, the animators were really able to work freely.

Adaptation of a popular tale and more particularly of the version written by Charles Perrault, Puss in Boots did not completely break with the system adopted during the production of Horus. The team was able to maintain the collaborative spirit that had allowed its members to get involved in the development of the project. Thus, some of the key animators drew the storyboard themselves, such as Kotabe who also animated the scene where Lucifer waits for the princess as well as the final scene.

Lucifer is waiting

The creation process of the film, however, illustrates a gradual change in the studio's policy on at least two points. The first concerns the growing importance of television for Tōei. The 2 scriptwriters in charge of the film were indeed busy with their work on TV series and it was the director - Kimio Yabuki - who had to complete the script.

The second point concerns the use of xerography, a method already used at Disney (in particular on One Hundred and One Dalmatians, released in 1961) and which allows to skip the stage during which the drawings made on paper are reproduced by hand on celluloid. The drawings on paper were now printed on celluloid (a transparent sheet on which the moving parts are painted), thus reducing production times and therefore costs, but with a drawback: at that time, the line was printed in black, whereas films that did not use it could adopt other colors to draw the outlines of the animated parts.

Puss in Boots was a success and Pero, its main character (designed by Mori), later became the emblem of Tōei, a sign of the film's popularity.

Released the same year as Puss in Boots, Flying Phantom Ship is an adaptation of a manga by Shōtarō Ishinomori, one of the most prolific authors of his generation and some of whose works had already been brought to the screen, big or small. This was the first time Hiroshi Ikeda and Kotabe worked as director and animation director, respectively, on a feature film.

Sketch of one of the main visuals of the film by Kotabe

After working on the series Himitsu no Akko-Chan (1969) and the feature film Alibaba to Yonjubiki no Tozuku (1971), Kotabe collaborated again with Ikeda on the movie Animal Treasure Island / Dōbutsu Takarajima (1971), an adaptation of the Robert Louis Stevenson novel Treasure Island. While Ikeda retained the role of director, Kotabe reverted to being a key animator, with the position of animation director going to Yasuji Mori. However, Kotabe's work on this film was one of the most influential of his entire career.

"We had to create an aesthetic to depict the sea, almost a main character in the story, which was a challenge. We could have stayed with the very realistic form we had on Horus, but it was a lot of work and very difficult for the animators. The director, Mr. Hiroshi Ikeda, gave me a month to think of a design and a way to simplify the waves to allow the whole team to work on its animation, and at the same time that suited the lightness of the story."

"When I asked him to find references, he gave me a whole folder of photos, advertisements, and other water-related materials. I was impressed that filmmakers are used to collecting this kind of stuff."

A ubiquitous element in the film, Kotabe had to look for a way to oversimplify the rendering of the sea and waves while still meeting the criteria imposed by Ikeda: "the dynamism, transparency, and warmth characteristic of the South Seas."

"Unlike Horus, where the curls of the waves are represented, as well as the effects of transparency, I opted here for simplification and a pleasant rendering. This representation has since spread to the industry; Miyazaki, who immediately appreciated it, still uses it today (in 2003). I would like to see his approach evolve into something else.

A flat color is used for most of the water while white represents the movement of the waves. A third color is sometimes added for the shadows

Numerous films and animation series have taken up the style defined by Kotabe on this film, his influence even extending to video games with games such as the very maritime The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker - again - which has transcribed it in its polygonal universe. One point, however, distinguishes the sea of the Animal Treasure Island from its descendants and for which Kotabe had to insist to convince his colleagues: its green color. In spite of all the material that Ikeda brought to him, it is in his memories that Kotabe went to dig to determine the color of the water, close to the one on which sailed the American transport ship which made him leave Taiwan when he was 8 years old.