Table of contents :

Part I: The Tōei era

Part II: From one studio to another

Part III: From animation to Nintendo

Part IV: Diversification and transmission

Part V: Towards new horizons

Sources

Appendix : Works on which Yōichi Kotabe has worked

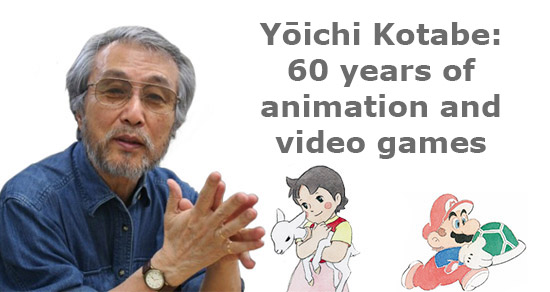

During the 80's and 90's, several personalities from the animation field moved to the video game industry. The connection between the two industries was already evident in the 1970s, although it became more visible in the following decade with celluloid illustrations commissioned from animation studios, whether for covers, promotional illustrations or drawings to be converted into pixels.

This was not the first time that an exodus from one entertainment industry to another occurred in Japan. In the 1960s, Osamu Tezuka had taken advantage of the fact that the system of book rental shops (Kashibonya), where you could find comics, had fallen into disuse to recruit some of his actors who were then in need of work.

For some artists, their time in the animation industry was quite short. Akiman, designer of many iconic characters for Capcom, worked for a few months at Miyuki Production (he animated a sequence of Road Blaster / Road Avenger, an arcade game on Laserdisc and produced by Data East) before being hired by Capcom, while Yasushi Yamaguchi worked as an inbetweener on the film Honneamise no Tsubasa / Royal Space Force then joined Sega where he designed the character of Tails, Sonic's faithful companion. The first one invoked the fact that the pay he received was not enough to cover his transportation costs and his rent.

Others had already accumulated years of experience in the animation industry, including Takatsuna Senba, who had served as animation co-director on Char's Counterattack (perhaps the most famous movie of the Gundam franchise) before joining Taito where he worked on Darius II and then directed the development of Metal Black, Gun Frontier and Dino Rex. Let's also mention Shuzilow Ha (Parodius, Twinbee), Hideki Tamura (Cotton) or Yoshinori Kanada, star animator of the 80's who joined Square (like others before him) to work on the movie Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within before moving to the video game branch, even if his work was mainly on game cinematics. The example of the latter is quite close to that of Don Bluth, animator and director who navigated between the animation and video game industries since the beginning of the 80s on the other side of the Pacific. He worked on games such as Dragon's Lair and Space Ace and directed many movies including The Secret of NIMH, An American Tail, among others.

All these former animators have in common that they have several strings to their bow and, for the majority of them, it is less for their ability to animate characters than for their talents as character designers or illustrators that they became known to the public.

Yet one of the very first people in the animation industry to collaborate with (and later join) the video game industry was not known for either of these skills.

A former film student specializing in neo-realism, Hiroshi Ikeda joined Tōei Dōga in 1959, at the same time as Yōichi Kotabe and Isao Takahata. Like the latter, he was not an animator per se, but a director as well as a scriptwriter, positions he held until the early 1970s. In 1972, while undergoing a global restructuring, Tōei transferred Ikeda to its newly established research and development (R&D) office.

Ikeda: "The research and development topics I had to deal with included various technological improvements, computerization of animation production, labor saving and automation.

Tōei Animation addressed the problem of productivity by reducing the workload. [...] I myself thought that if we wanted to improve productivity, we should automate production, reform drawing techniques, and improve the human resource development system."

This desire to reduce production costs had led, as early as 1966, to the adoption of xerography, a process already employed at Disney beginning in 1960. While Tōei sought to differentiate itself from the competition, and more particularly from the American giant, it did not forget to keep a watchful eye on the market. Thus, several members of the R&D office made the trip to the New York Institute of Technology to study the system developed by the future co-founder of Pixar, Ed Catmull, who was conducting research on automation through computers at the time. However, the implementation of this system would have been more expensive than the system then in use at Tōei, which therefore refused to adopt it. Ikeda did not give up on the idea of introducing computers into the animation industry and continued his research for almost a decade.

In the United States, some actors of the live-action film industry were already interested in the use of computer tools for the creation of films. Walter Murch, one of the most famous editors of his generation (he collaborated with Francis Ford Coppola on several occasions, notably on Apocalypse Now), explains in his book In the Blink of an Eye that he approached computer editing in 1968. Alas, these machines were then of an incomparable power to those of today, and the producers of The Godfather (1972) were not convinced when Coppola, George Lucas and Murch argued for this nascent system (there is, however, one shot in the movie in which a zoom was controlled by a computer).

In 1976, while still at Tōei, Ikeda began his collaboration with Nintendo.

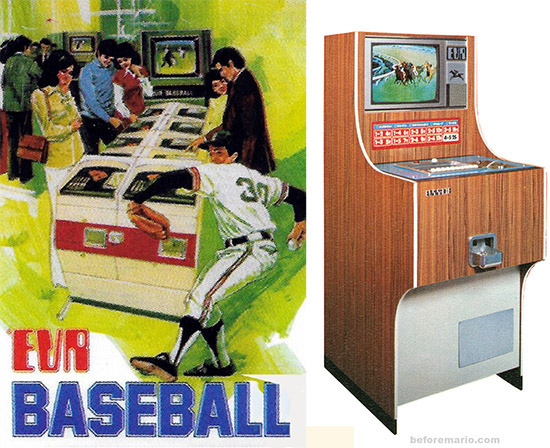

"My first contact with Nintendo was when I was in charge of the development of a baseball game using EVR support that was being developed jointly with Mitsubishi Denki."

As early as 1974, Nintendo developed a series of arcade games using live action footage held on 16mm film strips. The following year, the company took up the idea of video sequences but used another storage system developed in the United States: the EVR (for Electronic Video Recording). Several titles were released in the EVR range (EVR Baseball, EVR Race, itself declined in 2 versions), games of chance with limited interactivity in which the player bets on the outcome of a race or a match, the hazardous character of these titles residing in the fact that the sports sequences proposed by these terminals are read randomly by the machine.

If Hiroshi Ikeda worked on EVR Baseball, it seems that a member of another animation studio worked on the Derby version of EVR Race, considered by some people (including Shigeru Miyamoto) as the first video game developed by Nintendo. Indeed, Masayuki Uemura said at the 2005 Digital Interactive Entertainment Conference that the sequences of this title were animated by a famous person who was also a horse racing enthusiast. Historian Florent Gorges mentioned in the first volume of The History of Nintendo that this person was non other than Yōichi Kotabe.

One of the variants of EVR Baseball and the Derby version of EVR Race

The nature of Ikeda's involvement in the production of EVR Baseball, which succeeded EVR Race, is uncertain, as details of the nearly decade-long collaboration between Tōei and Nintendo have leaked little or nothing and the games are very difficult to access these days. However, it is likely that this was more of a relationship involving research and development than animation per se, although Tōei animators may have worked in this capacity on some of the EVR games.

If one were to venture a hypothesis, and knowing Ikeda's past record in computerization, it is not impossible that his office was in some way involved in the setting up within Nintendo of equipment for digitizing and converting drawings into sprites, a system that we know was already employed in 1984 on the arcade game Punch-Out!!.

Ikeda continues: "After that, we continued our relationship, and from about 1983, when Nintendo was developing the Famicom, I began to consult them more frequently. That's why I joined the company in 1985 as the head of Research & Development 4 (later renamed Nintendo Entertainment Analysis & Development)."

Like his fellow animators, Ikeda left Tōei with the realization that he could no longer do what he wanted there and decided to join Nintendo. He took over as head of R&D4 during the development of Super Mario Bros.

"When I joined the company in 1985, Nintendo's development organization consisted of development divisions 1 through 3, all of which dealt with both hardware and software. However, after introducing the Famicom to the market, we needed to strengthen our game development capabilities to provide new titles. For this purpose, the Entertainment Analysis & Development Department was created, to specialize in software development. I was invited to become the director of this department. However, I was not interested in game production at that time, and I still don't play (laughs).

I myself was responsible for the development as well as the management of the organization, but basically I thought it would be better to have separate people in charge of managing the organization on the one hand and producing works on the other, like in a film company. The two section heads under me were one in charge of management and the other in charge of development. The department head who specialized in development was Shigeru Miyamoto.

Soon, Ikeda brought in one of his former animation colleagues from Nintendo.

In the mid-1980s, Yōichi Kotabe found himself in a position that no longer suited him. After leaving several studios and going independent, he struggled to find interest in what he was doing.

"At the time, I was freelance, I was no longer part of the core team in charge of defining the lines of a project. It was a bit frustrating. And then, the trend in television animation was to cut costs and the number of images, quality was no longer the priority."

His lifestyle has also changed; he felt increasingly out of step with an industry that expects some of its employees to work overtime, something Kotabe now refused to do.

It is in this context that the one he calls friendly Ike-chan - Hiroshi Ikeda - made an appointment with him to propose him to join his new employer. Ikeda's request was simple: he was to train Nintendo's staff in movement.

"Mr. Ikeda said to me, 'Video games are at a stage where we're going to need more and more animator expertise, and we'd like you to join us and give us the benefit of your experience in this area.'

I didn't really want to go, but because of the frustration I was feeling, I thought, 'Why not go for a year or two.'"

At the time, Kotabe had very limited knowledge of video games. He had already heard of Space Invaders through his former colleague Yasuo Ōtsuka, but as he watched the game run, he wondered what interest there could be in it. His curiosity was only slightly more aroused by the Game & Watch that some of his relatives played.

"To tell you the truth, if at that time my work in animation had been interesting, I would not have turned to video games."

At 49, he decided to join Nintendo and, despite the skepticism and misunderstanding many of his former colleagues expressed about his change of career, his early days at the company quickly confirmed his choice.

"When Shigeru Miyamoto showed me Super Mario Bros., I was immediately taken by the interest of this character and this universe that put all kinds of movements into shape. I was convinced that the video game medium could qualitatively match that of cartoons and I felt able to apply my own animation experience to it."

"The worlds of video games and animation were becoming closer and closer and I thought this would be a good training for me."

Kotabe was not the first animator called upon to collaborate with Nintendo. As early as 1984, through Ikeda, the company called on Takao Kōzai, founder of Studio Juno and a former Tōei employee who had worked (among other things) on Animal Treasure Island, a film directed by Ikeda. Kōzai was responsible for drawing the characters for the arcade game Punch-Out!! on celluloid before they were adapted into pixels by Nintendo graphic designers. Minoru Maeda, another member of Studio Juno, made illustrations for the games Excitebike (1984) and The Legend of Zelda (presumably the first episode). However, like many animators after them, they have only occasionally worked with video game development companies. Nintendo expected a greater investment from Kotabe, even though he joined the company with the idea that he wouldn't be there for long.

"Nintendo asked me to move to Kyōto, but my wife didn't want to live there and, besides, we had children to take care of, so I flatly refused and they conceded that point."

Kotabe owes this special treatment to Ikeda, who had petitioned Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi to open a branch in Tokyo. Yamauchi granted his request and opened an office in Nihonbashi, a district more popular with businessmen than with animators or developers. It was not a new development studio, but rather a pied-à-terre rented by Nintendo, located on the second floor of a small building and devoid of computers.

"Mr. Ikeda had to convince the president that Tokyo was the center of information. He also named the office "Jōhō kaihatsu-shitsu" (Information Development Office) or something cool like that (laughs). I worked there, but my home base for game creation was Kyōto. I had to travel to Kyōto every week, which was also the case for Mr. Ikeda. Even though he was the head of Mario development, he was based in Tokyo and traveled to Kyōto once a week."

(Note: the name of the Tokyo office as given by Kotabe is very similar to the name adopted as early as 1989 by R&D4 - Jōhō Kaihatsu Honbu (called Nintendo Entertainment Analysis & Development in the rest of the world). Unless there is some confusion on his part, it is possible that this was one and the same division. It is also possible that the name of this office was the origin of the name that R&D4 took later)

Kotabe stopped working from home and joined Nintendo's Tokyo office at the end of 1985 as a development advisor, leaving his drawing board for a desk. At the same time, he traveled two days a week to Nintendo's headquarters in Kyōto to attend meetings and present the sketches he had made during the previous week.

"When I went to Kyōto several days a week, I was in contact with young recruits. There, I would usually draw whatever came to mind for games, not for game mechanics, but for things that seemed interesting. Sometimes they would even incorporate my ideas.

It wasn't formal meetings at all."

Among the tasks Kotabe was given was refining the characters in the Mario universe. When he joined Nintendo, Super Mario Bros. had already been released, but the game manual featured only rudimentary drawings, and the illustrations created for earlier titles such as Mario Bros., Wrecking Crew and Donkey Kong have obviously not been used as references by the animator. The cover art for Super Mario Bros., which was sketched by Miyamoto and finished by an illustrator whose identity is still unknown, was therefore the only starting point for Kotabe's work.

Promotional flyers for the Japanese versions of Donkey Kong and Mario Bros. and the cover of Super Mario Bros.

Kotabe adopted a rounded style and drew illustrations that convey a desire to make the characters feel the movement, to define their attitude, the way they act and move. Illustrating them in such a way helps to define them more precisely and to give them life.

The former Tōei employee had a lot of freedom in designing Mario, even though he regularly consulted Miyamoto.

"At the time, Mario was on a roll and there was a high demand for visuals from various industries.

"At first, I drew reference images for outside contractors, merchandise, stickers, etc. I would draw Mario dancing, wearing a new year's kimono, as a cowboy, etc."

Super Mario Bros. shoes illustrated by Gaku Miyao (Devil Hunter Yohko) and produced between the release of the game and the redesign work done by Kotabe

"I tried to follow Mr. Miyamoto's original idea as much as possible, but I tried to make it a little more three-dimensional, and to make the different facial expressions changeable."

"I kept the thick outline of the character. On the other hand, I accentuated the features of the 'M' on Mario's hat, to distinguish it from the McDonald's logo, which asked us, instead, if they could look more alike."

"I worked to give it a drawn look and in addition drew the cover illustrations. Since there was a big gap between the pixel version and the illustrated version of the character at the time, we had to have a lot of discussions and conversations with Mr. Miyamoto. We talked a lot about his nature, his personality, his dress code and all sorts of things. I didn't have any restrictions from Nintendo, except that Mario shouldn't kill and there shouldn't be any blood."

This directive reminded him of his work with Takahata on Heidi, with the director giving him - at best - only very brief descriptions for each of the characters in the series.

As for Peach, Miyamoto had a more precise idea of the character in mind and was more directive towards Kotabe, who drew the character in several times, according to the questions he asked and the answers and instructions he received.

Miyamoto : Peach completely changed. I told him everything I wanted, like how I wanted the eyes to be a little cat-like.

Kotabe : And how she should look stubborn.

Miyamoto : Stubborn, but charming. (rires)

Bowser is probably the one whose appearance has changed the most since his first appearance on the cover of Super Mario Bros. retaining only his imposing build and menacing air. Coincidentally, Miyamoto was inspired by a character from one of the first films Kotabe had worked on at the Tōei: Saiyūki / Alakazam, The Great..

Miyamoto : Bowser changed a lot, too. I'd been drawing Mario for quite a while, so there were a lot of things on how I wanted him to look like, but I hadn't drawn Bowser that much, so I couldn't get the lines to come together right. I like Toei Animation's work from around the time of Alakazam the Great, and the ox that appears in that...

Kotabe : The ox king. Miyamoto-san liked that ox, and that was how he imagined Bowser. When you see the package art he drew, Bowser does look a bit like an ox. But after that, Takashi Tezuka said...

Miyamoto : He said it was a turtle.

A little later and in the absence of Mario's co-creator, Kotabe confessed that he saw in this creature another type of animal:

"To me, it looked like a hippopotamus. So I took inspiration from the Chinese trionyx - the most aggressive turtle I know - and redesigned it to look really mean."

Character illustrations from the manual of the Japanese version of Super Mario Bros. 2

That leaves the fourth wheel of the tricycle, Luigi, a character who until then had been portrayed as Mario's perfect twin:

"I wanted to differentiate him, to have on the one hand a more dynamic Mario, full of energy, and a more timid Luigi, on the reserve."

The green-capped plumber was also the occasion for Kotabe to return to his first love: animation. Except that the short sequence he animated was supposed to be converted into pixels for integration into a video game.

Kotabe : For a while after I joined, I didn't work on animation at all. I showed up at work every day, and then sat around doodling whatever came to mind.

Miyamoto : If I remember correctly, the first animation Mr. Kotabe drew for us was of Luigi spinning around in circles. But we couldn't use that many frames, so we couldn't use it in a game.

Less than 3 years after the Famicom, Nintendo released the Famicom Disk System, an accessory that was supposed to extend the life of its console by freeing it from the 32kb limit that its game cartridges suffered from at the time. To accompany the release of this peripheral, Miyamoto and his team were working on a new title developed in parallel with Super Mario Bros. : The Legend of Zelda.

As was often the case at the time, it was decided to include an animated sequence in the TV commercial for the game. Its creation was entrusted to a studio located in Osaka, studio in which Kotabe went:

"The Legend of Zelda was the first Disk System game and we had to make a promotional video for it. So my first business trip took me to Osaka to supervise a promotional video production company. I didn't know anything about the game, so one of the people there came with me and gave me a presentation."

From the second episode - Zelda II: The Adventure of Link (1987) -, Kotabe was involved in the production of the game and was given the task of designing characters. It was probably under his pencil that the first version of adult Link was born. However, as was often the case during his career at Nintendo, he is not credited in the game, making it difficult to compile a comprehensive list of all the titles and work he was involved with. His employer was not necessarily worse than most of his competitors in this regard; it is quite common for illustrator and character designer positions to go uncredited in the end credits or in the game manual. The series of artbooks dedicated to The Legend of Zelda released in the 2010s has unfortunately not remedied this shortcoming, and the same is true for the Super Mario Bros. series, which was also the subject of a recently released encyclopedia.

It is therefore difficult to determine with certainty who made which illustration on the episodes of the series prior to Ocarina of Time (1998). Minoru Maeda is not credited on the first episode and it is not sure that he worked on the second one. As for Link's Awakening (1993), Kotabe is the only artist credited as illustrator, even though it seems likely that some of the official illustrations were finalized or even entirely made by one or several other people. As Yusuke Nakano pointed out in an interview conducted for the book The Legend of Zelda Art & Artifacts, "During the Famicom and Super Famicom era, many of the illustrations and manuals were made by external studios. At the time, the norm at Nintendo was to say, 'The final illustrations should be commissioned from professional illustrators!'" It wasn't until Ocarina of Time that illustrations were systematically done in-house, with the notable exception of the Game Boy Advance episodes developed by Capcom in the early 2000s.

Drawings probably made by Kotabe for Zelda II: The Adventure of Link and The Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening

The fact that an illustration was made by several people was not exceptional, in Japan as elsewhere. Artists such as Naoto Ohshima (Sonic The Hedgehog), Kazuko Shibuya (Final Fantasy IV) or Nobuteru Yuuki (Record of Lodoss War) were used to this in the early 90s. They made a pencil drawing then gave it to one or several people to reproduce it in color on a canvas or a combination of supports. In the second case, one person might trace and color the previously drawn characters on celluloid, while a third individual would paint the background on a sheet of paper. It is likely that the cover illustrations for the first three Zelda games were done by dividing the work between two or even three artists.

Starting with the Super NES episode - A Link to the Past (1991) - Kotabe was no longer the only Nintendo in-house artist to draw characters from this universe. He was now assisted by one of the artists he formed: Yoshiaki Koizumi.

Koizumi : "My first assignment was to do the art and layout and eventually the writing for the manual for The Legend of Zelda : A Link To The Past. What was funny was that at the time, it didn't seem like they'd really figured out what most of the game elements meant. So it was up to me to come up with story and things while I was working on the manual. So, for example, the design of the goddesses as well as the star sign associated with them."

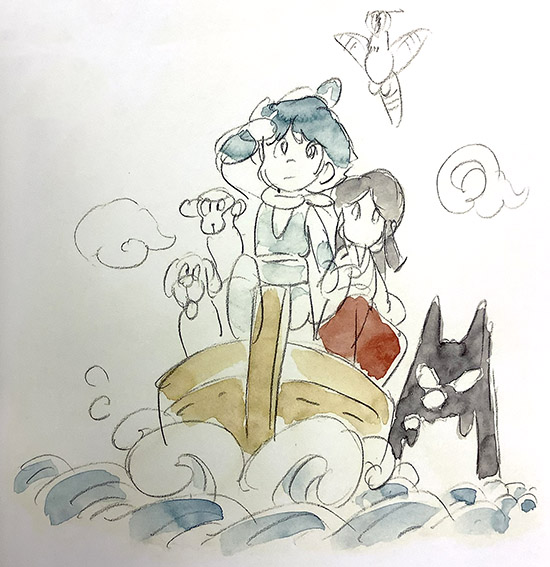

It seems that Kotabe produced new illustrations for an episode both before and after A Link To The Past : BS Zelda no Densetsu, the remake of the first Zelda released through Satellaview on Super Famicom. Illustrations probably made by four hands are featured in this 16-bit version divided into several parts and available for download since 1995. 5 people including Kotabe are credited as designers and one can notice a difference between the watercolor illustrations typical of Kotabe and reproduced in the book Hyrule Historia and those present in the game, probably digitized from "finalized" illustrations, colorized with another technique.

Watercolor illustrations probably painted by Kotabe for BS Zelda no Densetsu and their in-game version

Although he mainly worked with the Entertainment Analysis & Development department, to which Ikeda and Miyamoto were attached, Kotabe was sometimes called upon to collaborate with other departments at Nintendo, a sign of his singular status within the company. For example, he produced illustrations for Kid Icarus / Hikari Shinwa: Parutena no Kagami, the first episode of which was released in 1986 on Famicom Disk System (as well as on NES outside Japan).

The following year, he worked on a title that is better known to trivia fans than to Western gamers: Yume Kojo: Doki Doki Panic, which became Super Mario Bros. 2 when it was released in the West. For this game, Miyamoto once again took advantage of Kotabe's animation skills.

Miyamoto : I wanted the rug movement to be smooth. I wanted it to move like a real rug, and I thought I'd ask Mr. Kotabe. To Mr. Kotabe, the great illustrator, I said, 'Please, draw me a rug!'

Kotabe : So I drew him a rug that moved smoothly, and he told me it had too many frames!

Miyamoto : The original animation had over ten frames, but we needed to cut some out and repeat the same ones over and over so the frame count would be low but the rug's movement would be smooth.

That was the first video game work I ever requested from Mr. Kotabe.

The flying carpet of Yume Kojo: Doki Doki Panic in action

During the Disk System era, Nintendo produced several two-part adventure games such as the Famicom Tantei Club (1988), Shin Onigashima (1987) and Famicom Mukashi Banashi: Yūyūki (1989). The first one is probably the best known in the West, especially since the release of a remake on Switch (called Famicom Detective Club in our countries), but it is on the other two titles that Kotabe worked as a character designer. In addition, he also drew a sketch that served as the basis for the cover art of Shin Onigashima's second episode. As for Yūyūki, it was an opportunity for Kotabe to return to the novel Journey to the West, almost 3 decades after Saiyūki.

Shin Onigashima

Between Shin Onigashima and Yūyūki, the former animator made a more concrete yet very unofficial return to his original craft by working on the fourth animated feature film directed by Isao Takahata: Grave of the Fireflies.