Profile (aussi disponible en français)

Games

Other video game related works

To be confirmed

Other works

Gallery Part 1: games 1

Gallery Part 2: games 2

Gallery Part 3: non-video game related works

Gallery Part 4: “to be confirmed” section

Sources

Website

Website (old)

Related companies:

Sega

Profile

When we talk about illustrators working for video game companies, we more often hear about Capcom, SNK, Konami or Atari than about Sega, a company that has seen many talented artists pass through its doors. Apart from a handful of artbooks focusing on specific games or series (Sangokushi Taisen, Phantasy Star Online), only one book which, moreover, does not credit Sega’s in-house artists was published, in 1994: Sega TV Game Genga Gallery. The company rarely showcased its in-house artists, and some of them made a name for themselves only after going freelance, such as Pablo Uchida (Metal Gear Solid V, Death Stranding), Ryūichirō Kutsuzawa (Streets of Rage 3, Panzer Dragoon) and Ryo Kudou (GG Shinobi). Having remained with Sega for over 35 years, Taku Makino has not had the good fortune to see his name associated very often with the illustrations he has produced for his company and is very rarely interviewed, despite the range of talents he displays.

Born in 1960, Makino entered the video game industry relatively late, initially intending to pursue a career perceived by the general public as more artistic. After graduating from Tsukuba University of Art and Design, he began his career as an art teacher while painting canvases in his spare time. After a while, however, he decided to make a career change and joined Sega, where he started as a graphic designer in 1988. He joined the R&D 1 section (part of which became the AM1 department following a reorganisation around 1990), which was responsible for developing arcade games.

His first game as a graphic designer was the 1988 adaptation of Tetris, which became one of the most profitable games in the history of the Japanese arcade market. It remained in the top 10 highest-grossing games until 1997, and even topped the list until the release of Street Fighter II in 1991.

Makino animated the monkey who appeared in this adaptation and who returned in other versions of Tetris produced by Sega, such as Tetris S (Saturn), Sega Tetris (Arcade and Dreamcast), Tetris New Century (PS2) and Tetris Giant (Arcade).

Long unknown in the West, Sega’s adaptation of Tetris was so successful in Japan that it was one of the few games to appear in the company’s history on its official website in 2001, alongside Hang-On, Virtua Racing and Virtua Fighter (but without Sonic). In the West, this version remains much more confidential.

An adaptation for the Mega Drive was due to be released in March-April 1989, but due to the legal imbroglio surrounding the licence, Sega had to cancel the release at the last minute and destroy the stock of cartridges ready to be delivered to shops. Decades later, to embellish the Mega Drive Mini line-up, Sega and M2 produced a new adaptation of this arcade version for Mega Drive.

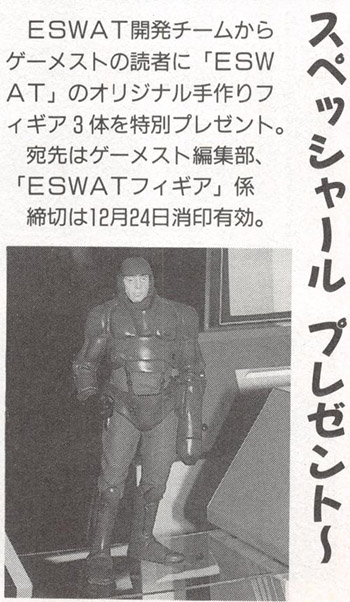

For the arcade version of Cyber Police ESWAT (1989), Makino again animated a monkey – a gorilla this time – with a sprite of imposing size (albeit smaller than the mecha-gorilla that appeared in Strider a few months earlier). During the development, he designed model figures in his spare time, three of which were offered as prizes in a contest. He also created the diorama featured on the game’s Japanese flyer, which was probably illustrated by himself. As a great fan of model figures, and more particularly of Maschinen Krieger, the influence of the world created by Kow Yokoyama on Makino was already apparent in his work.

With a very limited number of colours, Makino succeeded in giving the Cyber Police ESWAT gorilla body volume and a realistic appearance that was relatively close to the digitised sprites that Midway’s graphic designers were creating at the same time on the other side of the Pacific.

During this period, when he wasn’t painting in his spare time, Makino was producing model figures, some of which were marketed, including a dilophosaurus model kit released in the Art Modeling Collection.

When he’s not painting dinosaurs, Makino is sculpting them

These days, Makino seems to be at least as well known for his hobbies as for his career at Sega, and his reputation is as much for his paintings as for the figurines he makes. Apart from dinosaurs and mechas, he has produced a whole series of figurines based on the movie Blade Runner. Some of his creations have been featured in the magazines such as Hobby Japan and Armour Modeling, and he has won recognition from Yokoyama himself, among others. He is also a member of the Sega modelling club, where some of his admirers can be found (and where the diorama he created for ESWAT is kept).

After this Robocop cousin, Makino moved on to another arcade game whose Mega Drive version differed greatly from the original: Shadow Dancer (1990). This was his first foray into the Shinobi universe and, as with ESWAT, it’s very likely that he was once again responsible for illustrating the game’s Japanese flyer.

His fifth known game again featured a monkey – Bubble (which he animated once again) – but not only that: Sega of America had signed a contract with Michael Jackson to produce an arcade and console adaptation of the film Moonwalker.

For the arcade version (1990), the company asked its planners to submit adaptation proposals, but the person who had submitted the winning proposal – Yutaka Sugano – was working in the USA at the time, and management preferred to entrust the production of the game to someone based in Japan. With this in mind, producer Yoji Ishii asked Roppyaku Tsurumi, who had just left his job as editor at Beep! magazine to join Sega, to take charge of the project.

Because of the licence and Michael Jackson’s desire to be involved in the project, Sega of Japan had to communicate frequently about it with its American branch, which was in contact with the singer.

In the foreground, Makino on a Digitizer System III workstation. Michael Jackson, shown here with Mark Cerny (a former Sega of Japan employee who at the time headed up the Sega Technical Institute in the USA), met Makino several times during his career when he visited Sega of Japan.

Although Sugano’s project was chosen, the initial proposal underwent a number of changes during development, with some ideas being dropped (a segment in which the player could use a trackball to control the stage on which MJ was dancing) and others being added, notably some of those suggested by Makino. He drew and animated elements spontaneously, designed the game’s enemies, animated MJ and drew character illustrations in parallel with a combination of ballpoint pen and acrylic paint. According to Tsurumi, Makino was capable of doing twice as much work in half the time as anyone else.

Makino obviously didn’t try to stick to the world of the film when he designed the characters for the game, and the question of keeping his robots in the game was raised for some time within Sega

In the early 90s, Sega signed an agreement with Marvel to produce several adaptations of Spider-Man. Apart from the fact that the latter could finally officially join the cast of The Revenge of Shinobi temporarily without being dressed up in pink, he made a stint in the arcades in a game Makino worked on, the aptly named Spider-Man™: The Videogame (1991).

While the original plan was for a 2-player Strider-like game with Spider-Man and Black Cat as the main characters, Marvel negotiated 2 additional characters, namely Namor / Sub-Mariner and Hawkeye, which meant revising the game’s basics. It changed from a Strider-like game to a 4-player beat’em up. Tsurumi, who returned to the position of planner, tried to obtain other characters closer to the Spider-Man universe, but to no avail. He was not present during the negotiations, which took place in the US without Sega of Japan being involved.

Makino was one of the graphic designers working on the game and, as was sometimes the case in traditional animation (back in the days of The White Snake Enchantress in 1958, for example), he made a figure of one of the game’s bosses, Venom, to use as a reference for drawing and animating him.

The character seems to have become more muscular during his transition to 2D

Although Sega’s various development departments operated relatively autonomously from one another, Makino’s modeling talents became known beyond his department, and Naoto Ohshima asked him to create several Sonic figures while the first episode (1991) was still in development. Once again, the aim was to better define the character’s visual aspect, even though Ohshima was both the character’s designer and the person in charge of animating him.

One of these figures was used again as a model for the title screen of Sonic CD (1993). Some time later, Makino made a Knuckles figure that travelled to the United States, presumably to be used as a model for the pre-rendered 3D opening of Sonic & Knuckles (his name is listed in the special thanks section in the game’s staff roll).

Trained as an animator, Yasushi Yamaguchi apparently didn’t need to call on Makino’s services to design Tails, the series’ other star character.

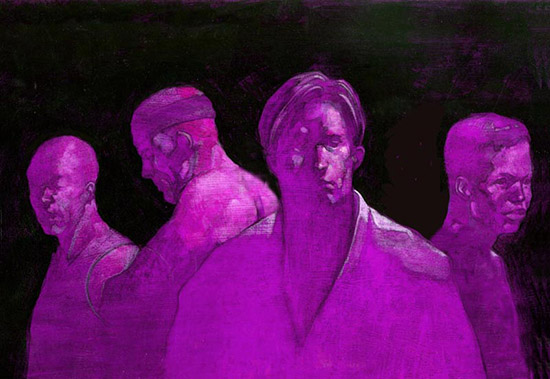

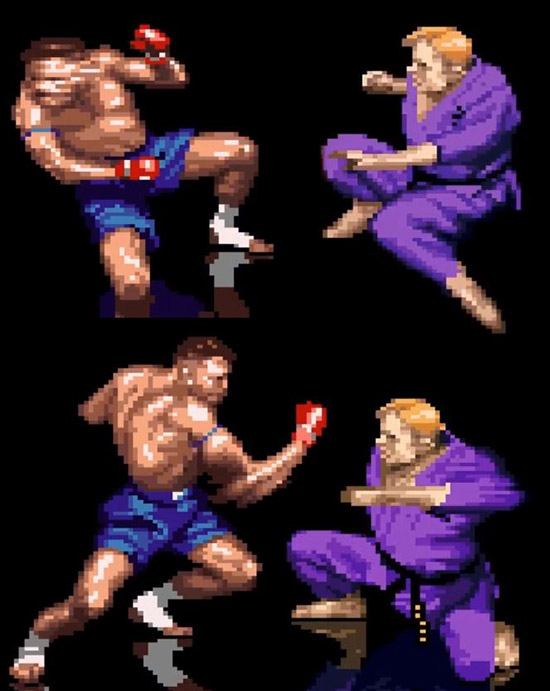

After a series of traditional 2D games, Makino followed up with a little-known project using holographic effects: Holloseum (1992). Released a year after Time Travellers, which made use of the same technology, this one-on-one fighting game running on Sega’s System 32 has a fairly limited number of characters, but features sprites with a level of detail that was uncommon at the time, and Makino’s style shines through in some if not all of them.

Character study by Makino

In addition, the animations of each of the blows and certain impacts contain smears. A smear is a process taken from traditional animation, consisting of a frame showing a deformation, exaggeration or blurring of movement in an animation cycle. Titles such as Golden Axe, Strider and TMNT, all released in the arcade in 1989, included smears to represent the movement of a blow with a bladed weapon (sword, axe, katana), and they could also be found in Sonic (the hedgehog’s running cycle) and Street Fighter II (Honda’s Hundred Hand Slap and Chun-Li’s equivalent with kicks) in 1991, but on a much smaller scale than in Holloseum. Nevertheless, they were relatively unostentatious compared with those Capcom artists later created for games such as Darkstalkers and X-Men: Children of the Atom (1994), which had a much more cartoony and exaggerated style.

Examples of smears

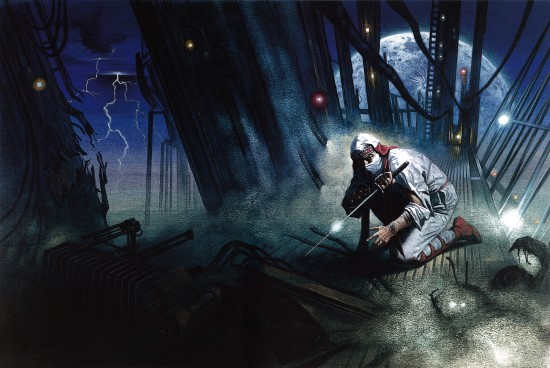

Also in 1992, Sega produced the arcade sequel to Golden Axe: The Revenge of Death Adder. Makino painted many illustrations influenced by Frank Frazetta, particularly in their composition or the way he depicted muscles, and the main illustration for The Revenge of Death Adder is clearly one of them.

Death Adder, a cousin of Frazetta’s Death dealer, with whom it shares the ability to have a face in backlight in all circumstances.

Golden Axe was already a well-known license in the industry, but Makino’s work, both as a graphic designer and illustrator, made him stand out from the crowd and got him noticed outside Sega, notably by Akiman, a Capcom artist who also shines with his range of talents.

Other artists Makino cites as references include the Italian Renaissance painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, pop-artist David Hockney, Vampirella comic artist José González, and Egon Schiele, whose influence is perhaps most apparent in the paintings the Sega employee creates outside working hours.

Since at least 1984, he has taken part in an annual art contest called Niki-kai, winning a number of prizes over the years. This is not his only work as an artist outside Sega, as he has also collaborated with Hobby Japan, illustrated an exhibition on dinosaurs and designed a book cover, among other things.

After being called upon for his modeling talents by a department other than his own, Makino was given the task of illustrating the box of a console game: The Super Shinobi II (AKA Shinobi III). Makino’s status within Sega then seems rather peculiar. The company had a design department (セガ・デザイン設計部) where several people worked on creating packaging and game instructions, but it only had one illustrator from 1991 to 1995: Mari Koizumi. At the time, Sega regularly called on outside illustrators such as Yuji Kaida, Yoshiaki Yoneshima, Akira Watanabe and Osamu Muto. What’s more, in-house graphic designers sometimes took charge of the illustrations for the games they were working on (Ryo Kudou, Masaki Segawa, Rieko Kodama), but Makino was in the much smaller category of graphic designers called in to carry out specific tasks on games on which they were not developers. One of the only other known examples is Yasushi Yamaguchi, who drew the box art for Bomber Raid (1989) without working on the game itself.

The Super Shinobi II

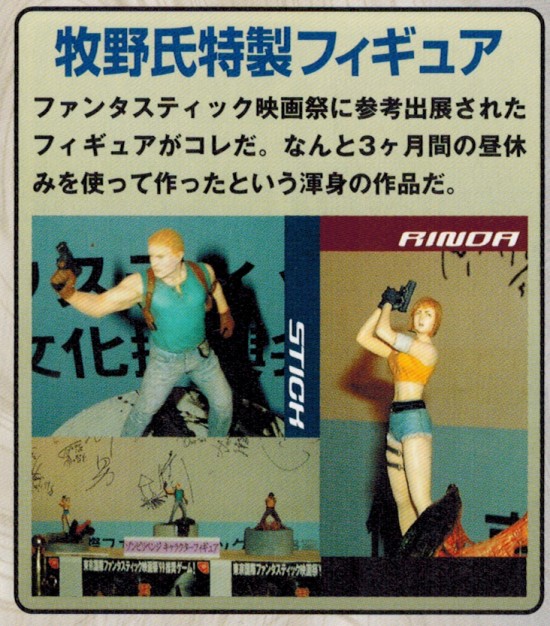

During the 90s, Makino continued to work on various arcade games, always making it difficult to draw up a complete list of them, as the inclusion of end credits was far less widespread than in console games (when they are not hidden behind a code, as is the case with Outrunners for example). He returned to the Golden Axe series with Golden Axe: The Duel, a one-on-one spin-off featuring the descendants of the characters from the first opus, then made his debut in 3D modeling with the Dynamite Baseball series (1996-97), Die Hard Arcade (1996) and Zombie Revenge (1999). For the latter, originally conceived as a spin-off of The House of the Dead, Makino supervised the creation of the characters, inspired by archetypes from American TV series. Once the arcade version was completed, he spent 3 months of every lunch break modelling figures of these characters, which were later exhibited at the Yubari Fantasy Film Festival in autumn 1999. The Dreamcast version should have been released during this festival but was postponed for a month. It was nevertheless shown on the big screen during an evening called Zombie Revenge: Horror All Night, during which the films Halloween H20 and Night of the Living Dead were screened.

Often used on the covers of games and magazines in Japan in the 1980s, model figures gradually disappeared from the marketing arsenal of video game companies in the following decade

A few years later, Makino actually worked on an episode of the House of the Dead series with the 2008 arcade game The House of the Dead EX, for which he designed the characters.

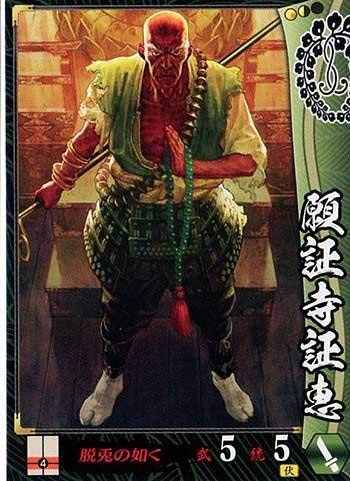

In the years that followed, Makino alternated between arcade and console games, and even mobile games. Despite his years of seniority at Sega, synonymous with additional rungs in the hierarchy of a Japanese company, he continued to carry out some of the tasks he was already performing in his early days. One of Sega’s flagship arcade series, launched in the mid-2000s, allowed him to paint more frequently at work, and to be credited in the same way as any other illustrator working on it. Sangokushi Taisen (2005) followed the card game craze that emerged in the 90s with titles such as Magic, Culdcept, Lord of Vermillion and Alteil, which saw a host of Japanese and even foreign illustrators called upon. A year earlier, Makino had already worked on a joint project with renowned artists such as Hiroaki Samura (Blade of the Immortal), Mahiro Maeda and Keita Amemiya on the PS2 adaptation of Osamu Tezuka’s manga Dororo (known as Blood Will Tell in the West).

In 2014, Makino gave an interview (the only one known to date) for one of Sega’s official websites in which he described his process of working as an illustrator on Sengoku Taisen (2010), another arcade card game:

“The very first step is a sketch drawn in a pocket notebook with a ballpoint pen. […] Sometimes I draw with my index finger using a drawing software on my phone. […]

I often draw in the bathroom or during meetings! I draw sketches in my spare time and finish the rest in Photoshop. I don’t know how to separate layers, so I don’t scan my sketches, and I redo them from scratch in Photoshop.“

For this illustration, Makino posed in front of his mirror to draw hands, but holding the pose too long caused his hand to tense up and he hurt himself. So he asked one of his colleagues to pose for him.

At around 65, Makino is slowly approaching retirement but still seems to be driven by the same passion for art, continuing to make figurines for his own pleasure or for his friends, and painting on canvases larger than himself as well as on his phone or an iPad. In 2022, he resumed his previous career by giving painting lessons twice a month in Yokohama. We hope he continues to create for a long time to come.

Taku Makino with two of his paintings (2014)