You are in museum. All around you are presented works from different times and places, some famous, others less so. During your visit, you hear here and there people praise their aesthetic qualities, while noticing that their talk often run out of steam after only a few superlatives. You quickly realize that the museum labels placed under each of these works have no indication as to the identity of their author. You inquire at the reception where you’re answered that it’s not an omission and that it's a recurrent phenomenon. You retort that these are contemporary works and that their respective artists, at least some of them, are probably still alive and that there is surely a way to trace them, but your interlocutor gives you a shrug as his only answer.

In the space of a few decades, the video game industry has managed to attract some of the best contemporary artists and craftmens (composers, illustrators, concept artists, architects); nevertheless, it remains a field in which they are often as invisible as script doctors in cinema, ghost writers in literature or some comickers’ assistants (especially, but not exclusively, in Japan).

Even today, this sector is still struggling to solve its anonymization problem. Although for many developers and artists it was (and sometimes still is) a personal choice, most of the time that decision came from management to prevent employee poaching.

In 2013, Naoto Ohshima suggested that the use of pseudonyms may have been a way to prevent artists from claiming copyrights on their creations.

Although the designers are paid more than when the Japanese market welcomed Hello Kitty (whose creator was just one of the many employees working at Sanrio), legally speaking, even today, every work created within a company is the property of that company.

When asked about the identity of the illustrator behind Fighting Ex Layer a few weeks before the game’s release, Arika’s Vice President Ichiro Mihara answered that, to get the answer, you would have to buy the game and watch the end credits. A fairly widespread attitude in an industry where many companies fear that letting some of their employees appear in the foreground could lead to a clash of egos which obviously wouldn’t be conducive to teamwork.

Whatever the reasons, illustrators often find themselves draped in the same cloak of invisibility. Websites such as GDRI, GameStaff@wiki and VGMDB have been struggling for years to find the identity of subcontracting companies, developers and composers neglected by staff rolls or credited under a pseudonym they have not necessarily chosen, but the situation of illustrators is somewhat different. Cover illustrations are often perceived not as a component of the games but as a promotional tool, which probably explains why the artists’ names are often omitted from the game credits.

However, this rule knows a significant number of exceptions depending on whether or not the illustrator 1) is a member of the company that produces the game, 2) is a famous artist, 3) took charge of the design of the characters.

What follows is not a miracle solution -even by taking precautions, it is almost impossible to obtain absolute proof that such artist is the author of a given work- but a presentation of the method I use, with the aim of putting a name on every video game related artworks.

I ] Searching for the author of an illustration

During the first half of the nineteenth century, John Smith undertook a census of the works of Rembrandt and drew up a corpus of nearly 600 paintings, a number that fluctuated (sometimes by several hundreds) according to the research done by his successors.

In 1968, experts founded the Rembrandt Research Project to catalogue more precisely the list of works of the Dutch painter, to whom the authorship of some paintings has sometimes been wrongly attributed. Among those originally categorized as one of his works is The man with the golden helmet, a painting whose author’s identity remains unknown.

The man with the golden helmet (~1650)

The Rembrandt Research Project often relied on preparatory sketches to determine the authorship of a work, but this technique is not infallible and the fact that video games are often collaborative works minimizes the significance of this kind of clue.

The techniques used by the Comité d'Authentification des œuvres d’Hergé (authentication committee of Hergé's works), founded in 2010, are also difficult to transpose to the video game sector. Although this committee aims to identify documents made by different people -many comic books signed Hergé including Tintin were written and drawn with the help of other authors such as Edgar P. Jacobs (Blake and Mortimer), Jacques Martin (Alix) or Bob de Moor- and whether they are contemporary artists, it focuses on a group of artists whose identity is already known to its members. However, there is currently no exhaustive list of people who work or worked in the video game industry. What's more, collaborations do not necessarily happen within the same company. Thus, Satoshi Nakai, graphic designer and independent designer, has in his portfolio a drawing whose design is pretty much the same as the one featured on the Assault Suits Valken cover illustration. However, that illustration was made by Masami Ohnishi, another independent illustrator.

Design created for Assault Suits Valken (Super Famicom, 1992) followed by the game cover art

Although it's obvious that we can hardly apply the same analysis techniques to the video game sector, especially since the relevant artworks are generally visible only through reproductions - the originals are either on digital files, or in the hands of companies or individuals and are publicly exhibited only on rare occasions - we can still try to establish criteria adapted to our research and to our time.

First thing to look at: does the name of the illustrator appear somewhere in the game, the manual, the cover or on a paper ad?

In 1981, to illustrate the flyer of its arcade game Bosconian, Namco contacted Shusei Nagaoka, an artist who had designed record sleeves in the 70s for Deep Purple, George Clinton, Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) or Earth, Wind & Fire. His name is featured on the flyer, which is not the case of the logo designer -Hiroshi Ono, AKA Mr Dotman- an in-house artist.

Bosconian flyer (1981). The artist’s name is written under the illustration (”イラスト: 長岡秀星 “)

Yoshiaki Yoneshima created illustrations for several Mega Drive games including Bare Knuckle I and II, Golden Axe or Super Monaco GP. The main source of information regarding this artist is a book -Sega TV Game Genga Gallery-, but his contribution to Tatsujin was confirmed thanks to the game manual (with an approximate conversion of his name in rōmaji).

Excerpt from the Japanese manual from Tatsujin (1989)

Akira Watanabe has collaborated on numerous occasions with Jaleco and Sega, especially on the Sonic series. His work is not systematically credited, but his involvement in various episodes of the Outrun series is generally indicated on the box of these games.

Fragment of the Turbo Outrun cover (Mega Drive, 1992)

Eternal Arcadia, also known as Skies of Arcadia, is an unusual case. The staff roll credits Itsuki Hoshi for the illustrations but the artist who made the promotional artworks used before the game's release -Shinichi Morioka- isn't credited anywhere.

Skies of Arcadia’s staff roll (2000)

Is the illustration signed?

There is no absolute rule. Some artists, even famous, never sign their works. Even if you concentrate your efforts on one publisher, you can find signed illustrations while others aren’t. Sometimes an artist is not allowed to sign his full name and only put his initials.

Cover illustration of the Atari 2600 version of Vanguard (1982), designed by Ralph McQuarrie, concept artist who became famous thanks to his work on Star Wars

When a famous artist works on a game, he is frequently credited on the game cover, on a paper ad or in the staff roll, sometimes even on the start screen, either because he imposed such a close in his contract (as usually does the composer Yuzo Koshiro), or because his involvement constitutes a marketing argument -in Japan more than elsewhere, the name of the artist(s) involved in a project is often mentioned in the game previews. Akira Toriyama was one of the first artists put forward in Japan with the release of Dragon Quest in 1986, although renowned artists such as Kow Yokoyama (sculptor and mecha-designer), Mutsumi Inomata (animator) or Jun Suemi (illustrator) had already put a foot in the video game industry before him.

Dragon Quest (1986)

It would be risky to attribute to an artist the paternity of a work on the sole basis of his initials, especially if these are written in a neutral calligraphic style, even though the art style is similar to that of the artist. At most we can draw from this bundle of indicators a high probability.

El Coloso, a work originally attributed to Francisco de Goya and whose authorship was contested in 2008 partly because of the presence of initials with uncertain meaning

The fact that a signature is not visible on the jacket of a game doesn’t mean that the illustration hasn’t been signed. An unfortunate tendency -which is especially evident in the West- is to hide the artist's signature with a logo, a text or a cropped image, when it is not purely and simply erased.

The signature of the artist in charge of the illustration for the Mega Drive version of Strider -WC- appears on a Brazilian ad

Some artists change their signature in the course of their career, others use several simultaneously.

It also happens that an artist changes his name or pen name. Although we usually call him Bengus, the former Capcom artist has regularly changed his pseudonym during his career (and continues to do so on Twitter): CRMK, Mido Shiito, Holy Homerun, Gouda Cheese, etc.

Another type of change, more specific to Japan: the change of spelling. For the sake of simplicity, many artists write their name not in kanji but in hiragana. Sometimes, an artist whose name includes an unusual kanji substitutes it with a simpler kanji that can pronounce in the same way. Satoshi Nakai, illustrator on the Culdcept series has used no less than 3 different spellings since the beginning of his career:

中井 覺, simplified in 中井 覚 then changed to 仲井さとし

Indicating the Japanese spelling is a good way to limit the risks of confusion between 2 homonyms.

On the left, a drawing by Hisashi Eguchi / 江口寿史. On the right, a drawing by Hisashi Eguchi / 江口寿志.

Another case that was not uncommon in the early 90s in Japan: the dual identity. Kensuke Suzuki debuted with a Western-inspired style, influenced by artists such as Frank Frazzeta and Jeffrey Catherine Jones. In parallel with this style, he began to draw illustrations with a more rounded style, more in keeping with the perception that one could have of the Japanese style, in particular on the Shining Force Gaiden and the Dragon Master Silk series for which he signed his artworks Hiroshi Kajiyama.

Shining Force Gaiden and Dragon Warrior II, the American version of Dragon Quest II

In the 1970s, the Hildebrandt brothers made themselves known thanks to their Lord of the rings illustrations made with 4 hands and signed by both. Although they went their separate ways in the 1980s, they nonetheless collaborated several times on game illustrations.

Other, more occasional collaborations have been set up, notably in the United States where distributing tasks (line, inking, colorization) is quasi-institutional in the comic book industry. It is not uncommon to find illustrations signed by two or three artists, especially for comic book adaptations made in the 80s and 90s. However, this distribution is sometimes done between in-house and outside artists. This is what happened on the first episode of F-Zero for which the comic strip featured in the manual was sketched by Takaya Imamura, while artists from the studio Valiant comics handled the final version.

Preparatory and final versions of the F-Zero comics (1990)

If the illustrator also takes charge of the character design, chances are that it will be credited in the game, without necessarily mentioning the illustrations. Nevertheless, it frequently happens that the artist in charge of the illustrations (including the character illustrations featured in the manual) is a different person from the one or those who designed the characters. Such is the case in most fighting games produced by Capcom, SNK or many other companies, as well as in other types of game (Langrisser, Shining Force III, the Golden Sun series, etc.).

The very special case of the illustration retouched by an unidentified person:

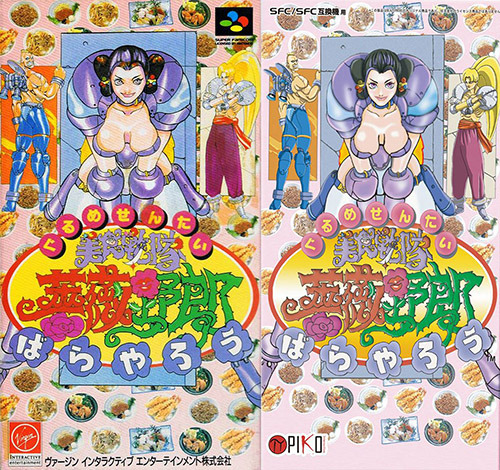

In January 2018, Piko Interactive reissued the Super Famicom game Sentai Gourmet with a packaging that, logos and legal notices aside, looks identical to the original at first glance. Except that by looking a little closer, you realize that the cover illustration is not quite the same. Is it a recolorization or a complete re-creation of the illustration? Did the original author took charge of this? Important notice regarding the present case: it's not excluded that the original artwork is missing or unavailable. Tomoharu Saitō, one of the artists behind the game and who was credited as illustrator on other titles, passed away in 2006. The identity of the original illustrator is still unknown to me.

Gourmet Sentai: Bishoku Sentai Bara Yarō (1995), original versus reprint version

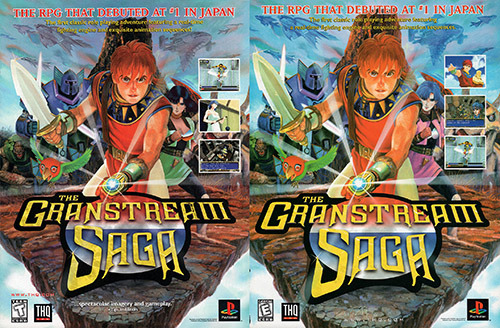

Other illustrations for titles such as Street Fighter II and Grandstream Saga have been modified a posteriori. This practice is often associated with George Lucas, who brought it into the spotlight with Star Wars, but the phenomenon is older than that. From Tintin and Bilbo the Hobbit to Blade Runner, Gunnm / Battle Angel Alita or Pierre Bonnard who sneaked into galleries to retouch his own paintings, the reasons given for such changes are at least as numerous as there are artistic fields involved.

Street Fighter II (1991) and The Grandstream Saga (1997) - spot the 2-3 differences

In case there isn't any mention of the artist's name in the game, the manual, the box or the related advertisements, several options are open to the researcher.

Use the "search Google for this image" function (basic feature available in Chrome) to:

_check that the illustration in question has not been used in another version of the game. If the artist's name is indicated somewhere, it is usually in the original version, but sometimes this kind of information can be found in a later version (ex: Gradius II on X68000).

_check that the illustration in question has not been used in another medium. Examples: tabletop RPG, movie posters, Choose Your Own Adventure books, CD covers, etc.

_realize that, besides being totally useless for your research, Pinterest monopolizes the first pages of results

Search for goodies and related products:

_OST: sometimes illustrators are credited in the booklet of the game's OST

_artbook: 3 limits:

1) some artbooks credit only the company behind this or that game when the illustrations are made by (an) in-house artist(s).

2) incomplete credits: the cover art of the Japanese version of Sonic 1 was finalized by Akira Watanabe, an illustrator who worked for an agency in contract with Sega. While his name appears in the artbook Sega TV Game Genga Gallery, this is not the case of Naoto Ohshima, an in-house designer who made the sketch that served as the basis for this illustration.

Another case that may explain why a name is missing: the illustrator had already left the company that made the game when the artbook was being made.

3) Mistakes: At the time of the Vampire Art Works artbook's release in 2013, Akiman revealed that the information he gave during the interview conducted for this book had been poorly collected as his interlocutor didn't manage to record the whole conversation and had to rely on his own memory to transcribe what had been said.

Information published in a book are not necessarily more valuable than those published on a personal blog or on Twitter, it all depends on the source.

Illustration made for the Spring 1994 issue of the magazine Club Capcom. The game depicted here -Forgotten Worlds- was released in 1988, while the illustration itself is dated December 3, 1993. Although it was featured in at least two Capcom-dedicated artbooks in addition to the aforementioned magazine, the identity of the author of this illustration remains unknown

Is the illustrator an employee of the company that produces the game?

In 1984, Capcom contracted an outside company to design the flyer illustration of its first arcade game: Vulgus. Despite a 2 million yens check, the result was considered unconvincing and the management decided that, from then on, the illustrations would be made internally (which did not prevent the company to collaborate with artists such as Tetsuo Hara and Hirohiko Haraki years later). The names of the Capcom illustrators never appear on the illustrations themselves (with the notable exception of the one made for the Street Fighter I flyer, signed Seiya.), but some of them managed to make a (pen)name for themselves through the 1995 artbook Gamest Mook 17: Capcom Illustrations which has been followed by other books dedicated to the company or some of its games. Before that, the only way these artist had to make themselves known was to put their signature on drawings included in newsletters and fan letters.

Gamest Mook 17: Capcom Illustrations (1995)

During the second half of the 1980s, other companies such as Sega allowed their employees to express themselves through newsletters (SPEC), while SNK opted for handwritten manuals dedicated to some of its arcade games (Athena, Ikari Warriors, Psycho Soldier, etc.). Moreover, like his neighbor Capcom, SNK's management probably realized that it had an interest in promoting its in-house artists, thus making another contribution to the rivalry between these two fighting game specialists. A few artbooks began to appear in the mid-90s, although only a handful of artists under pseudonym were credited (Shinkiro and Eiji Shiroi).

Note that companies with a department dedicated to illustration and design sometimes contract external artists to create artworks, be it for marketing reasons or because their in-house artists are overloaded with other tasks.

Excerpt from the manual published by SNK for its 1986 arcade game Athena. Rampty, the illustrator and author of the comic book included in this book, is credited twice in it

Shadow Dancer illustration created by Yasushi Yamaguchi, AKA Judy Totoya, featured in the 7th issue of SPEC

Search the name and nationality of the publisher:

Some publishers often use the same artist(s). During the NES era, the American branch of Vic Tokai generally worked with Lawrence Fletcher to design its game cover illustrations.

Most of the time, Japanese publishers contract Japanese artists. Of course there are a few known exceptions, but putting the Japanese game illustrations published in a separate folder is a good way to limit the area of research.

Do a Google or Twitter search with the game’s name:

First point: keep in mind that unsourced information has no value. Then, it's up to you to do your own haphazard research. This can lead you to a personal site, an interview, a message from the author or one of his collaborators, or pictures of an exhibition dedicated to an artist or group of artists, a game or series of games or a company.

Victim of appearances, this illustration created for the sequel to the Dr Slump manga, too often attributed to Akira Toriyama, even though its author -Katsuyoshi Nakatsuru- is credited in the book in which it appears.

Auctions:

On 17 January 1995, the Great Hanshin earthquake struck Kobe and its surroundings with full force, killing several thousand people. Konami, which had set up its headquarters there in 1986, underwent major material damage and lost much of its archives, including illustrations made for the first episodes of the Castlevania series. In the absence of a public report, we do not know which other works have been reduced to dust; the inventory is being made bit by bit, either when the company celebrates the anniversary of some of its games (Gradius in 2015) or when originals works are auctioned, as was the case in 2017 with illustrations made by Hideaki Kodama for various Konami produced games.

Cover art for Contra III (1992), auctioned in 2017

Auctioning a work often makes it possible to discover the identity of its author and appreciate unedited illustrations, but the phenomenon remains uncommon, particularly in Japan. It also lead us to ask ourselves what type of contract the company and the artists established. According to Masaaki Kikuno, a former Konami graphic designer, its employer used external illustrators. In such a case, the same company can opt alternatively for two solutions: ordering an illustration from an artist that it can reproduce or, more expensively, ordering an illustration of which it will obtain ownership (which implies that the original will no longer be in the possession of the artist but of the company).

II ] Drawing up a profile

During the research I conducted regarding various artists, I found that many of them, including some of the most famous, had not been the subject of extensive research to date. The profiles drawn up here and there were generally incomplete or inaccurate and the sources rarely mentioned.

The first step in profiling is to find a trace of the artist concerned on the Internet. Google's algorithm tends to show Wikipedia pages, Google and Twitter accounts before personal sites; However, the latter are the first thing you should look at. Some artists have a website that exhaustively lists their various works; others are more laconic as their aim is to highlight their most recent works. In the second case, archive.org can be useful to list old news or discover that an author had a page listing some if not all his works in the past.

The trend of having a personal website suffered from the arrival of social networks in the second half of the 2000s and many sites have not been updated or have been shut down since then. Cases of URLs not saved by archive.org are unfortunately frequent (assuming that you have managed to find a URL somewhere).

Example of a website still online on October 1, 2018 but which had not been archived by Archive.org since 2005. The site will close in a few months (in March 2019) along with all the other sites of its host, Geocities Japan

Another issue that may be encountered is that some artists see their video game related works as casual jobs and do not seek to highlight them.

If the previous step was not entirely satisfactory, turn to printed materials. The artist you're doing research on may have published artbooks, which sometimes include a list of works and interviews. Searching on Google, Amazon or suruga-ya.jp (for books published in Japan) should be enough to find out about the existence of such books. This may require a certain budget, especially for authors whose works are spread over a dozen books (Katsuya Terada is a good example).

Regarding interviews, those published on paper may have not been mentioned by anyone on Internet; hearing about them may be a matter of pure luck and putting your hands on them isn't necessarily easier. As for those published on the Internet, the same problem as with personal sites may occur: they have sometimes disappeared with the sites that hosted them and archive.org may not be able to get them back, illustrating the need not to wait to do this kind of research.

If you still don't get any positive results, the next step is (basically) to visit the Internet: do a search with the author's name in Google, Twitter and Facebook, in 2 languages if the artist is Japanese, in which case you can add sites such as Famitsu and Game.Watch.impress to your searches.

These searches should make it possible to find new games, rule out rumours, obtain confirmations or even see what work the artist has done on a particular game. For the last point, it is often necessary to do a search for every game on the said websites (spoiler: this can be very long).

Why not contact the author?

Sometimes, the difference between a biographer and a stalker boils down to a question of point of view. Some artists may feel uncomfortable when someone is digging into their past, especially if they have moved on (left the industry, changed their name or nickname, etc.). Others are delighted to see that someone appreciate their past works and share spontaneously information or correct some details, especially on Twitter. I prefer to contact only people in the second category.

Most of the time, developers have entered the video game industry without thinking that decades later, people would remember their work or even seek to know more about them. Many want to remain anonymous and obviously do not realize that it can be easy to find their name via Mobygames or an equivalent simply by having a list of some of the games they have worked on and mentioned on Twitter or elsewhere.

How can I avoid missing out on some games?

Unless you have a collection that will make the Great Library of Alexandria pale, you won't be able to claim to be exhaustive; exhaustivity is an ideal, your aim is to collect as much info as possible. To minimize risks, the best solution is to collect pictures: cover illustrations, leaflets, magazines, advertisements, etc.

Collecting pictures is also a good way to discover new artists. When you collect information about one game in particular, you may discover that there is not one but several illustrators credited on the same game, which is very common for trading card games (Culdcept, Lord of Vermilion, Alteil, etc.).

Collecting pictures makes it possible in the best of cases to find illustrations with the artist's name on it. Sometimes you will only find a signature. However, the most frequent case is the absence of a name and signature. Collecting this last type of pictures can lead you to detect a style common to several illustrations. Imagine that you have the artist's name for one of these illustrations and that another illustration with a similar style is unidentified; the chances of getting a confirmation will be higher by Googling the second picture with the artist's name. Of course, if your guess is wrong, you won't find anything.

Most artists don't limit themselves to only one area, which means that you can take a look at other fields and extend your research to people whose main work isn't necessary illustrator to discover new artists: magazines (Dragon Magazine, Animage), card games (Magic) movie posters, comickers (mainly in the comics and manga circuit), key animators in the Japanese animation industry, etc.

Sources:

Naoto Ohshima on the use of pseudonyms:

The untold History of Japanese game developers Vol.3 p300

Ichiro Mihara on the identity of the illustrator behind Fighting Ex Layer:

https://twitter.com/miharasan/status/998426929291132928

Rembrandt Reasearch Project:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rembrandt_Research_Project

Comité d'Authentification des oeuvres d’Hergé

https://fr.tintin.com/contacts/expertise

Satoshi Nakai and Valken:

The untold History of Japanese game developers Vol.2 p251

Masami Ohnishi and Valken:

https://twitter.com/Captain_Pixel/status/954543987670491138

Mega Drive manuals and cover art:

https://segaretro.org/

Vanguard and Ralph McQuarrie:

Tim Lapetino - Art of Atari

El Coloso:

https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-colossus/2a678f69-fbdd-409c-8959-5c873f8feb82

Satoshi Nakai:

https://web.archive.org/web/20061212153509/http://home.n00.itscom.net/dnb/profile2002.html

https://twitter.com/ariga_megamix/status/535731341321437184

The untold History of Japanese game developers Vol.2

Sonic CD:

https://twitter.com/eguchi_1203/status/839576418581241856

Kensuke Suzuki - Hiroshi Kajiyama:

https://twitter.com/KAJIYAMA_/status/486427966780346368

https://twitter.com/daza_e5656/status/499435833938550784

Tim & Greg Hildebrandt:

https://timhildebrandt.net/alpha.html

http://www.brothershildebrandt.com/Brothers.htm

F-Zero:

http://www.nintendo.com/super-nes-classic/interview-f-zero/

http://jimshooter.com/2012/02/made-to-order.html/

Tomoharu Saitō - Gourmet Sentai:

http://www.la-saito.com/

Gradius II:

The Official art of Gradius II

Akira Watanabe - Naoto Ohshima:

Sega TV game genga gallery

https://twitter.com/NaotoOhshima/status/847131989392031744

https://twitter.com/NaotoOhshima/status/850292613504577536

Lack of reliability of some artbooks:

https://twitter.com/akiman7/status/312911990144258049

Capcom and Vulgus:

https://twitter.com/akiman7/status/303439055343992834

The Capcom Fan Club:

http://shmuplations.com/capcom1991/

Forgotten Worlds:

https://twitter.com/e_capcom/status/912616075489042432

Capcom Illustrations:

https://web.archive.org/web/20160121001940/http://www.capcom.co.jp/game/content/?p=5358

Athena:

https://retrogamegoods.com/gamegoods_item/snkエスエヌケイ「アテナ」攻略マニュアル

SPEC:

https://segaretro.org/Sega_Players_Enjoy_Club

Konami and the great Hanshin earthquake:

https://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/134653/where_games_go_to_sleep_the_game_.php

Hideaki Kodama:

http://forums.lostlevels.org/viewtopic.php?t=3539

Konami hired external illustrators:

The untold History of Japanese game developers Vol.1 p184